Estimated reading time: 21 minutes

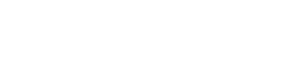

The primary reason most people build a shelter from natural materials is because they have to. A sudden shift in the weather on a long hike, getting lost after wandering off-trail, or the common nemesis of darkness falling long before you find your way back to camp.

In most instances, an improvised natural shelter is made in the wilderness. That’s fortunate because there's usually a good supply of natural materials surrounding you if you know what to look for.

In this post, I'll describe a few different types of survival shelters built from natural materials and which ones is best for which situations.

Want to save this post for later? Click Here to Pin it on Pinterest!

Types of Wilderness Shelters

Most wilderness shelters made from natural materials have been inspired by thousands of years of experience. It’s no surprise that the first homes were improvised shelters, and in a time long before lumberyards and stores like Home Depot, nature was the only source of materials.

Many of these shelters reflect the area and the availability of natural materials, while others reflect the weather conditions or basic lack of natural resources. An igloo or snow shelter is a good example. In places where few trees grow and grass is buried under snow, the ice became the only source for constructing a shelter.

Other designs seem to be driven by common sense as logs or branches were leaned against a long, low branch or a support to create the iconic lean-to. Native people developed their own designs from teepees to wigwams, huts, and a lucky few who managed to find the perfect cave.

Related: How to Survive If You’re Stranded in the Winter Wilderness

Naturally Occurring Shelters

Speaking of caves, they’re a good example of a naturally occurring shelter. Sometimes you need to find shelter fast, and while there are many YouTube videos of people taking a day or two to craft a beautiful shelter out of natural materials, it does little to help you during a torrential rain or blinding blizzard.

If you can find an accident of nature that provides some level of shelter, you have a head start on finding some protection from the elements.

You could also take a little time at some point to improve or use one of these natural solutions to enhance the shelter.

Examples include a large tree supported above the ground by its roots and branches. Make sure it’s safe, but if all looks well, the trunk of the tree can keep you out of the rain, or the nest of roots and the hollow under the root ball can keep you out of the wind and rain.

Related: 10 Natural Survival Shelters To Look For In The Wild

Pines trees provide natural protection from snow, especially when growing in a grove, and the base of a many pines create their own shelter around the trunk as snow accumulates on the boughs.

A cliff overhang is more common and can protect you from wind and rain, depending on the direction, and is another example of a natural structure that is easily improved with the addition of some branches leaned against the top of the overhang.

Then again, there’s always the off-chance that you find one of those caves, but be careful. Many types of animals recognize the value of a cave as a shelter, from skunks to bears. Neither is something you want to confront unexpectedly.

Worse, caves are notoriously dark once you enter, and steep drop-offs and slopes are common. Shout into the cave and throw a few rocks before entering. Better yet, illuminate it with a flashlight or flaming torch and advance slowly. If you see glimmering eyes in the distance or a slick, downward incline, slowly back out.

Shelter Materials

Trees are the most common source of natural materials for shelter building, but there’s more to a tree than just branches. If you have an axe or hatchet, you’re really in luck because you can fashion just about anything you need from the tree.

Related: How to Make Stone Tools

If you’re without equipment, you’ll have to depend on deadfalls, branches that break easily, and leaves, boughs, or bark that is easily peeled. And that gets to how each one of those components should be considered for a shelter.

The Trunk

The trunk of a tree that has fallen to the ground can give you a quick way to make a lean-to. If the trunk is elevated horizontally along the ground, you could lean branches on either side to create an A-frame. That’s a good move for trees with smaller diameter trunks.

The Bark

The trunk of any tree also gives you bark. The best use for bark is for shingles for your shelter. Remember to start stacking your shingles at the bottom and overlapping them as they go up. This will allow the bark to shed rain like the shingles on a house.

Bark can also be used on wet ground or snow to create a water-resistant layer between you and the cold and wet. Large slabs of bark from a large, dead trunk can also be used as a simple door or cover to keep wind and rain out of your entry and exit point to the shelter.

Related: 9 Survival Tools You Can Make From Tree Bark

Strips of bark can also be braided into cordage. Spartacus and his slave army wove ropes from tree bark to escape the Romans, and if it worked for Spartacus it can work for all of us.

And unless you are in a life-or-death emergency, be careful about stripping bark from a living tree. If you strip all of the bark around the circumference of a tree, that will kill it. It’s called girdling, and it was used by ancient people to kill a tree before felling it with fire and stone axes.

The Branches

The size and flexibility of branches vary, and that’s a good thing. A thicker, sturdier branch can be used for support. Thinner branches can be woven into a lattice work to create the foundation of a roof or wall. Flexible branches, especially from trees like willow, can be woven into an even tighter lattice and also used as cordage.

The branches from pine trees can be used to make a soft and insulated bed. Pine boughs on sheets of bark can go a long way to keeping you warm when the ground is cold or covered with snow. It makes sense to scrape the snow ground a bit first, but even then the ground will be chilling without some bark and boughs as a bed.

The Leaves

The leaves of a tree are another excellent, natural material for bedding in a shelter. They can also be used on the roof and around the sides of a shelter as well.

You may need to pile some branches carefully across the leaves so they don’t blow away in the wind, but once in place they can block the wind, keep the snow out and do at least a decent job of keeping you from getting soaked by rain. They will drip a bit, but they may eventually mat and cause the rain to run off.

And don’t forget pine needles. The forest floor under a pine forest is usually covered with a layer of dead pine needles. They make excellent bedding on the floor of your shelter, and will not only cushion the ground and keep you dry but have an insulating quality that can also keep you somewhat warm.

The Sap

Pine sap or pitch is nature’s glue. Look for it on the trunks of pine trees where cuts, scrapes, or broken branches show up. It can be used to hold parts and pieces of a shelter together where gravity or cordage need a little help.

You could also drill a hole into a maple tree with a knife or narrow piece of flint or chert and collect some sap from the maple and other deciduous trees in early spring, assuming you have some way to collect the drops.

A hollow reed stuck into the drilled hole will direct the droplets into any container you have or improvise whether it’s a bark cup or a small piece of a branch hollowed out with burning coals and a knife.

Most sap is not only safe to drink but actually has a few calories due to the natural sugars. Maples are best, but birch, boxelder, alder, and even black walnut all have sap often used to make syrup. Avoid drinking sap from any pine or conifers. That’s sometimes used to make turpentine.

The Roots

If you come across a large, uprooted tree, the roots can actually be used to help build a shelter. You’ll need a saw or an axe because roots tend to be very dense and hard, but their intricate curved shape and spiking off-shoots can be interlocked and joined to make the structure for a shelter.

How big the shelter ends up being depends on the size of the roots, but if you’ve ever seen the roots of a large, uprooted tree, you know how big they can get.

Best Shelters by Season

In a primitive or wilderness environment, the primary need for a shelter is to protect you from the elements. This could be blistering hot summer heat and sun, bone-chilling cold and wind, relentless snow, or constant rain. What’s true is that some types of shelters offer better protection from some of those elements than others.

In a pinch, any shelter is better than none but if you know what’s coming or it’s a certain time of year, it’s wise to think ahead.

Summer Heat

The goal here is to avoid the direct rays of the sun and allow for at least some exposure to breezes that can keep you cool. Location has a lot to do with those factors, and it’s fair to say that the shade of tree can work, but if you’re in a desert or grassy plains, those trees may be few and far between.

Even in a forested environment, there are periods of sun and shade, and a shelter can keep you in the shade all day long.

Lean-to

A lean-to is a fast and easy shelter to build, especially if you only need some shade. You don’t have to fuss too much about waterproofing it to keep out rain and snow, and it can give you a place to rest, eat, sleep, and keep you somewhat cool.

Direction is important, and the slanted roof should be facing south to shade you from the sun in summer.

The build is fairly straightforward and starts with a long, thick tree branch propped into branches on two trees about 8 feet apart or two large tripods about 8 feet apart and about 5 feet high.

The cross beam or support branch or log is either supported by the triangle at the top of the tripods, held up by branches or a “Y” in the trunk of the tree, or lashed with bark cordage to the trees. Make sure you use plenty of cordage and lash tightly because this cross-beam will be supporting everything you lean against it.

In a pinch, you could also cut two long branches that end in a “Y’ and drive the bottoms into the ground with the “Y’s” at the top to support your cross beam.

Another thing to consider is using larger logs to brace the sides of the roof. Think of these as the primary roof supports containing all other branches leaned onto the roof.

After you’ve got your cross beam and primary roof supports in place you simply lean branches against it.

Try to select straight branches and any overhang over the beam is okay because that will create more shade.

Continue the build until you have a fairly solid leaning roof over the area where you’ll sit or sleep.

Lashing some branches across the leaning branches and fastening them with some bark cordage will keep them in place in a strong wind.

The final step is to cover the leaning roof branches with leaves or slabs of bark to give you some solid shade.

The sides are left open to provide some cross-ventilation from any prevailing wind.

Leaves on the ground can give you some cushioning and more leaves stuffed into a t-shirt could actually give you a decent pillow.

Because it often gets cool at night, even in the middle of summer, the lean-to can also keep you warm with a fire built in a rock fire pit in front. It can also be used for cooking if you’ve got some food.

If wind or precipitation become a problem, you can lean some more logs or branches on an angle towards the opening to help close off the space.

Winter Snow and Cold

This is where things get serious. If you’re out in the snow and cold with no way to put up a shelter other than to build your own, you need to consider some options. Quickly.

If snow is on the ground, you’re also going to have some challenges finding natural materials. Sometimes dead branches still on the tree are easier to find and chop or break off. You can also look for branches poking up from the snow. If you see that, it’s a good bet there’s a small tree trunk on the ground underneath.

Leaves and grasses may be buried under the snow, but pine boughs are not only easy to see and harvest, their “ever green” nature makes them always available.

White pine is best because their long needles will compact if piled thick enough.

The A-Frame

One option is the A-Frame. It’s basically a long ridge pole supported on a rock or tripod with thick branches leaned across the ridge pole in descending lengths.

It eventually tapers down to the ground as the lengths of the branches leaned against the ridge pole decrease.

Leaves or grass or bark can be then layered or tossed on top to enclose the A-frame.

Pine boughs layered across the top is another option, especially when the snow has buried leaves and grasses, although pine boughs aren’t as effective at blocking the wind unless you really lay them on thick.

A fire pit is built in front of the opening and the finished A-Frame shelter provides protection from the wind, cold, and snow.

Igloo or Snow Fort

Most of us remember building snow forts in the backyard as kids. If the snow is wet, you can roll up some snow into a circle and continue building the walls one large snowball at a time.

Pack the cracks with snow and use it as mortar to hold your snow shelter together.

If you are stumped by how to finish a dome on your igloo (it’s actually very difficult to do) you can lay branches across the top until the roof is able to support more snow.

The snow is then packed a bit on top of the snow shelter and an opening is left at the bottom so you can get in and out.

A fire is not an option with a shelter made from snow, at least not in close proximity. You could always build a fire pit some distance away to warm up, but you’ll need to head inside at some point.

You also need to fashion some sort of door out of a large piece of bark, a cut stump, or a lattice woven from branches and pine boughs. Whatever you can find or fashion to block the cold and wind from getting into your snow shelter will work.

The good news is that it will be warmer inside than outside, especially when it comes to protection from cold winds.

The bad news is that it will never be toasty warm. At best it will get into the high 30’s, mostly because of the generated body heat from the occupants. However, if the temperature and wind-chill outside is below 0, an interior temperature in the 30’s will be welcome relief.

Don’t get cocky and start to think that rocks warmed in a fire would be a good idea inside a snow shelter. If temps get into the 40’s and 50’s inside, the snow will begin to melt and drip on you. Getting wet in winter is never a good idea.

Teepee

A shelter type that can actually let you have a fire inside in winter is the teepee. The construction is fairly simple, assuming you have a lot of small trees in the area and the tools to chop and cut them.

A teepee starts with 3 long trees about 3 to 4-inches in diameter. The length can vary from 10 to 16 feet, and the longer the better. It just depends on how many small tree trunks and branches you can find that are that length and relatively straight.

The 3 long trunks are lashed together about 1 to 2 feet from the top with cordage made from braded bark, thin willow branches, vines or even your belt or strips of fabric torn from your t-shirt.

The 3 trunks are then stood up and slowly moved out to form a large tripod.

More long branches and trunks are leaned against the tripod notch at the top around the circumference of the teepee until you have a fairly solid teepee construction.

Pine boughs, leaves, bark (especially birch bark) are then applied to the outer frame of the teepee. You can use a combination of anything available to create some wind and water proofing on the sides as a roof.

Remember to keep an opening towards the base so you can get in and out, and if you want a fire inside, you’ll need an opening at the top for the smoke to escape.

Any fire you build inside a teepee should be a small fire or it will become too hot or fill the teepee with smoke. A lot will depend on the wood you burn (dead, dry softwoods like pine are best) and the relative air pressure. Low pressure causes smoke to hug the ground, but high pressure will cause the smoke to easily rise to the top and vent.

Other Things to Consider

Sitting on the ground in a newly constructed shelter is one thing, but making things at least a little bit more comfortable is another. Here are some quick thoughts on how to make any night in a natural shelter a little easier.

Fire Pit

A fire in any camp is welcome and in winter absolutely necessary. Here are some links to a couple of articles that cover the range of fires you can put together to make your natural shelter a little more comfortable.

Bough Bedding

Pine boughs make excellent bedding in a natural shelter. So do leaves, pine needles, grasses, moss, and anything else in the vicinity that is soft, dry, and has some insulation properties.

If the ground and everything on it is wet, leaves torn from branches or pine boughs are a great solution.

Doors and Coverings

No matter what kind of shelter you build or what kind of materials you use, you have to be able to get in and out. The only problem is that the shelter opening can let the wind, snow, rain, and cold into your shelter.

Think about how to close off your entrance with bark, woven branches, even a wood pile. And wouldn’t it be great if you had a poncho to throw over the door.

Roofing Variations

The biggest challenge with most natural shelters is making it water and windproof. Regardless of the natural materials you’ve used, most natural materials are not perfectly straight, and gaps in the construction are inevitable.

Pay special attention to the roof and combine materials if you’re not sure. That mud and straw solution we mentioned earlier is worth remembering, but if time is short, pile everything on it and hope for the best.

Practice

If you’ve never built a shelter from natural materials, it’s worth trying it at least once. If you have kids, they’ll be happy to help.

Related: Teach Survival Skills to Your Children Using Miniatures

This is good stuff to know, whether you're active in the outdoors or just want to spend a few nights camping int he backyard.

Like this post? Don't Forget to Pin It On Pinterest!

You May Also Like: